It’s no secret that the highlight of my experience at HIFF42 was the screening of Lee Jung-jae’s HUNT (HIFF42 Centerpiece), which, as of writing this article, is now available on-demand online (I strongly recommend it!). So, given that I am neither Korean, nor am I particularly familiar with Korean history, I decided to look into the historical context of Hunt to broaden my understanding of the film.

To this end, I familiarized myself with one of the historical events that HUNT narrativized: The Gwangju Uprising of 1980. What I found both fascinated me and added a layer of complexity to an already complex film, which only deepened my appreciation for it.

I also feel obligated to emphasize that I am approaching this matter from an outsider’s perspective, and while I base the below information on an academic source, I am by no means an authority on this matter.

Nevertheless, spoilers ahead!

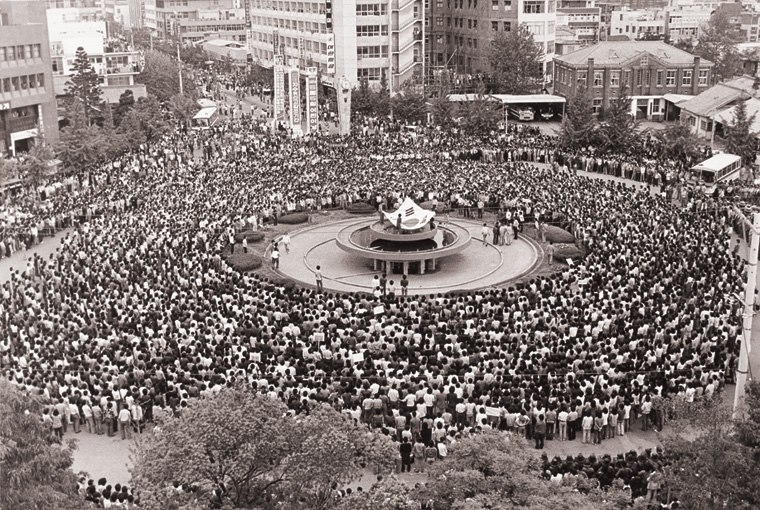

Arguably the most important event relating to HUNT’s story, despite occurring years before the events of the film, is the Gwangju Uprising in late May, 1980. This uprising was a reaction to a military coup that occurred in December of the previous year, following the assassination of the authoritarian president Park Chung Hee on October 26th, 1979 by the head of the Korean Centrial Intelligence Agency. Seemingly replacing one military dictator with another, many citizens and students resisted the authority of the new president, Chun Doo Hwan.

Between the days of May 18th and May 27th, what began as civil disobedience and protest would spiral into bloody violence as the South Korean Paratroopers were deployed to quell the resistance in an operation titled “Splendid Vacation”. These soldiers would beat, humiliate, arrest, and murder South Korean citizens under the notion that these dissidents were communists under the direction of North Korea, and were therefore enemies of the state (this notion of brutality in the name of Anti-Communism is especially present in the background of Hunt) (Kim, 611 – 612).

The Gwangju Uprising remains a traumatic event in South Korean history, having only been recognized as a “uprising for democracy” and not a “disturbance” since 2003, twenty years after the fact (Kim, 616). The reason for this, to my understanding, is because there was a general incapability for this domestic conflict to fit the “Us vs Them” paradigm that most conflicts can be fit into (Kim, 616 – 618). This is because many soldiers and officers who enacted the massacre would come to realize the injustice that they had participated in and acknowledge their own guilt, as well as the virtue in those that they victimized (Kim, 612).

HUNT comments on this contradiction in a very fascinating way through the character of Kim Jung-do (played by Jung Woo-sung). Jung-do, prior to becoming the Domestic Unit chief for the KCIA, was a military man who is revealed to have participated in the brutality of “Splendid Vacation”, and has externalized the horror of what he and other soldiers were lead to do into a hatred of the institution he works for. He, and his other military co-conspirators, resolved the “Us vs Them” paradox by identifying neither the uprisers as “the enemy” nor taking the blame unto themselves, but rather asserting that they were mislead and otherwise compelled to enact the slaughter by their president, and it was the trauma of this event that cemented their belief that the powers-that-be were despotic beyond reformation.

Now, it’s important to note that this isn’t necessarily the view of Hunt itself. As per my previous article discussing Hunt (which you can read here), the film doesn’t seem to whole-heartedly agree with Jung-do’s vengeful course of action. While the film clearly frames his reaction to this traumatic event sympathetically, Jung-do still remains antagonistic, with the narrative’s perspective seemingly favoring Park Pyong-ho’s disillusionment with bloody revolution. This perspective of resisting violence as a means to facilitate the exchange of power isn’t without its own justification. After all, Jung-do’s assassination attempt does echo the very same circumstances that directly lead to the Gwanju Uprising and the bloodshed of “Splendid

Vacation”, thus suggesting a circular ouroboros-like quality to the relationship between violent revolution and tyranny.

Primary source/Further suggested Reading:

Kim, Hang. “The Commemoration of the Gwangju Uprising: Of the Remnants in the Nation States’ Historical Memory.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, vol. 12, no. 4, 2011, pp. 611–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2011.603923

My name is David Murray. A resident of O’ahu for nearly my entire life, I am currently a Senior at UH Manoa working towards my Bachelors of Arts in Creative Media, but I previously studied English at University of Montana Western. I plan on pursuing a master’s degree in screenwriting and/or Film studies. On a personal note, I am abit of a genre nerd, with a special interest in Horror, Animation, and Cult films. While my aspirations lie in higher education (and hopefully a career in Screenwriting), it is also my goal to write and create content about pieces of media (Film, Television, etc.) that captivate me or otherwise would be unlikely to garner any serious academic attention.

My name is David Murray. A resident of O’ahu for nearly my entire life, I am currently a Senior at UH Manoa working towards my Bachelors of Arts in Creative Media, but I previously studied English at University of Montana Western. I plan on pursuing a master’s degree in screenwriting and/or Film studies. On a personal note, I am abit of a genre nerd, with a special interest in Horror, Animation, and Cult films. While my aspirations lie in higher education (and hopefully a career in Screenwriting), it is also my goal to write and create content about pieces of media (Film, Television, etc.) that captivate me or otherwise would be unlikely to garner any serious academic attention.

The mission of the HIFF ONLINE CREATIVES & CRITICS IMMERSIVE (HOCCI) program is to encourage film criticism in Hawai‘i by using the influencer branding strategies to spark career opportunities in the State and not be hampered by oceans, state borders and distance, because geography is no longer a barrier. Ten mentees participated in this program, giving them press industry access to HIFF42. In addition, the cohort attended mentoring sessions by working critics in the online film journalism community in unique silos: Writing, Podcasting, Video Essays and Vlogging.

Mahalo to DBEDT Creative Industries and Creative Lab Hawaii for their support.